The “Gospel” in the New Testament and the Qur’ān

What is a “gospel”? And what is “the Gospel”? And where is “the Gospel”?

The English word gospel is derived from the Old English gōd-spell (good news), which is a word-for-word translation of the Greek word “εὐαγγέλιον” [euangelion], which has the identical meaning.

Among the four Evangelists, the term “gospel” was used by only Mark and Matthew, and it was heavily used before that by Paul in the epistles ascribed to him. Although the noun was used many times, we cannot find in the New Testament any direct or clear definition of it. What we can detect is that it had different meanings in the communities that received the New Testament texts. These significant differences make the term problematic.

“The gospel” in the epistles of Paul is an abstraction that is attributed to different beings: “the gospel of God” (Rom. 1:1; 15:16; 2Cor. 11:7), “the gospel of Christ” (Rom. 15:19; 1Cor. 9:12; 2Cor. 2:12; 9:13; 10:14; Phil. 1:27; 1Thess. 3:2), or “the gospel of his Son” (Rom. 1:9). Paul refers to “my gospel” (Rom. 2:16; 16:25) and “our gospel” (2Cor. 4:3) and affirms that there is “no other gospel” (Gal. 1:7). He talks too about “the gospel” (Rom. 10:16; 11:28; 1Cor. 4:15; 9:14, 18). [1]

The meanings of the term “gospel” in the New Testament are extremely various. Here are some examples of its different connotations.

- The kingdom of God is at hand (Mark 1:14-15)

- The good news of what God has done on behalf of humanity in Christ (Romans 1:1-4)

- The narrative of Jesus’ life/message (Mark 1:1)

- The story told about Jesus after his death and resurrection (Galatians 1:11-12)

The conflicting meanings of the term “gospel”[2] tell us that this word, as it appears in the New Testament, is essentially ambiguous. Jesus used the term in one way, which differs from the way it was used by the later communities who dealt with the oral tradition without strict rules.

The existence of conflicting meanings for key terms like “gospel” in the New Testament reveals clearly that the transmission of the message of Jesus to the generations who lived after his ascension has a severe lack of fidelity and clarity. This is a perplexing phenomenon that needs much study in order to determine its source and motive. It is easy to see that the situation in regard to the word “gospel” is similar to those for other knotty New Testament terms such as “the Son of man,” and paraklētos, “παράκλητος” (commonly translated as “comforter” or “advocate”), which lost their clear meanings when they were inserted into the New Testament text.

“The Son of man” as a religious term was borrowed from the Old Testament, where it is connected with the end of time (Book of Daniel). In the New Testament, this same term is transformed into three distinct and incompatible meanings: Apocalyptic Sayings, the Son of man will descend to earth to gather the elect and to judge; (2) Passion Sayings, the suffering and defeated Son of man; and (3) Sayings Connected with Jesus’ Ministry. The third group of Son of man sayings is the most heterogeneous, but all refer to some aspect of Jesus’ earthly ministry.[3]

Another striking example is the word parakletos; Johannes Behm, in The Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, writes, “The use of the term παράκλητος in the NT, though restricted to the Johannine writings, does not make any consistent impression, nor does it fit smoothly into the history of the word as described [earlier]. In 1 John 2:1, where Jesus Christ is called the παράκλητος of sinning Christians before the Father, the meaning is obviously “advocate,” and the image of a trial before God’s court determines the meaning. In John 16:7-11 (cf. 15:26) we again find the idea of a trial in which the Paraclete, the Spirit, appears (16:8-11). The Spirit, however, is not the defender of the disciples before God – nor the advocate of God or Christ before men, which involves an unwarranted shift of thought – but their counsel in relation to the world. Nor is the legal metaphor adhered to strictly. What is said about the sending, activity and nature of this paraclete (16:7, 16:13-15, 15:26, 14:14 f, 14:26) belongs to a very different sphere, and here (cf. Jesus in 14:16) παράκλητος seems to have the broad and general sense of “helper.” The only thing one can say for certain is that the sense of “comforter” […] does not fit any of the NT passages. Neither Jesus nor the Spirit is described as “comforter.” [4]

In the Qur’ān, “the gospel” is a holy scripture sent down by God to his prophet Jesus as guidance to the Israeli people. It is a verbal inspi-ration to Jesus from God through Gabriel, the Holy Spirit.

The essence of “the gospel” in the Islamic lexicon can be found in three Qur’ānic verses,

{وَقَفَّيْنَا عَلَى آثَارِهِم بِعَيسَى ابْنِ مَرْيَمَ مُصَدِّقًا لِّمَا بَيْنَ يَدَيْهِ مِنَ التَّوْرَاةِ وَآتَيْنَاهُ الإِنجِيلَ فِيهِ هُدًى وَنُورٌ وَمُصَدِّقًا لِّمَا بَيْنَ يَدَيْهِ مِنَ التَّوْرَاةِ وَهُدًى وَمَوْعِظَةً لِّلْمُتَّقِين وَلْيَحْكُمْ أَهْلُ الإِنجِيلِ بِمَا أَنزَلَ اللّهُ فِيهِ وَمَن لَّمْ يَحْكُم بِمَا أَنزَلَ اللّهُ فَأُوْلَـئِكَ هُمُ الْفَاسِقُون}

“And in their footsteps, We sent Jesus the son of Mary, confirming the Law that had come before him: We sent him the Gospel: therein was guidance and light, a confirmation of the Law that had come before him: a guidance and an admonition to those who fear God. Let the People of the Gospel judge by that which Allah hath revealed therein. If any do fail to judge (by the light of) what Allah hath revealed they are (no better than) those who rebel.” Q: 5:46-7

{وَمُصَدِّقًا لِّمَا بَيْنَ يَدَيَّ مِنَ التَّوْرَاةِ وَلأُحِلَّ لَكُم بَعْضَ الَّذِي حُرِّمَ عَلَيْكُمْ وَجِئْتُكُم بِآيَةٍ مِّن رَّبِّكُمْ فَاتَّقُواْ اللّهَ وَأَطِيعُون}

“(I come to you) to attest the Law which was before me. And to make lawful to you a part of what was (before) forbidden to you. I have come to you with a Sign from your Lord. So fear Allah and obey me.” Q. 3:50

So, Jesus’ Gospel is (1) a written book (2) coming from God (3) that ordered the Israeli nation to obey the Torah commandments (4) with a few exceptions, by making lawful some of that which had been forbidden before.

The Qur’ānic stress on the similarity between the Gospel, al-Injīl, and the Torah can be seen in the joining of these two words nine times. The word al-Injīl occurs in the Qur’ān, by itself, only three times. So we can see that the Gospel and the Torah share many fundamental features.

The Lost Gospel

The majority of scholars agree that the first three Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) are not books composed fresh from their authors’ pens. Each is the final stage of a prior live oral tradition, not a pure product of these three authors.

Daniel B. Wallace acknowledges that “it is quite impossible to hold that the three synoptic gospels were completely independent from each other. In the least, they had to have shared a common oral tradition. But the vast bulk of NT scholars today would argue for much more than that. […] it is quite impossible—and ultimately destructive of the faith—to maintain that there is total independence among the gospel writers.”[5]

In the quest for the earliest sources, scholars inaugurated what is called “the synoptic problem,” which is an attempt to explain the similarity of the books of Matthew, Mark, and Luke to each other over against John.[6] The latest in-depth studies show that the synoptic problem is one of the most intriguing problems of New Testament scholarship, and that it has, of a certainty, not been resolved.[7] We will review some of the theories that tend to resolve the synoptic problem to show how delicate the situation is and to show that these theories are based on indirect proofs.

(1) The Two-Source Hypothesis. This is the most common solution proposed for the synoptic problem, and it is based on three pillars:

- Mark is the first written Gospel, and the source for Matthew and Luke.

- There is a hypothetical document composed in Greek that contains a number of “sayings.” It is called Q, short for the German Quelle, meaning “source.”

- Matthew and Luke composed their respective books independently.[8]

(2) The Farrer Theory. Farrer accepted the priority of Mark as proposed by the Two-Source Hypothesis, but rejected the Q hypothesis, and proposed, as an alternative, the idea that Luke had used the books of Matthew and Mark. He stated, “The Q hypothesis is not, of itself, a probable hypothesis. It is simply the sole alternative to the supposition that St. Luke had read St. Matthew (or vice versa). It needs no refutation except the demonstration that its alternative is possible. It hangs on a single thread; cut that, and it falls by its own weight.”[9]

(3) The Two-Gospel Hypothesis. It is a theory submitted by Griesbach and propounded again, in its current form, by William Farmer. The solution claims the priority of Matthew, and that Luke depended on Matthew when he wrote his Gospel, and that Mark was the last composed Gospel written as a conflation of Matthew and Luke.[10]

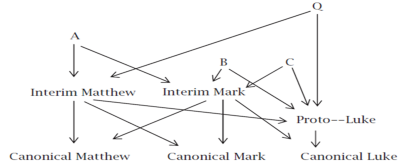

(4) The Theory of M.-E. Boismard. This is a complex elaboration of the Two-Source Hypothesis, involving multiple editions and levels of interrelationship.[11] Boismard proposes “a Palestinian proto-gospel (A) a Gentile–Christian revision of it (B), and an early independent document, perhaps from Palestine (C) as well as the Q sayings source, an “interim Matthew” (dependent on A and Q), an “interim Mark” (dependent on A, B, and C), and a “proto-Luke” (dependent on “interim Matthew,” B, C, and Q). Canonical Matthew is thus dependent on “interim Mark” and “interim Matthew.” Canonical Mark is at least dependent on “interim Mark” with perhaps a link to “interim Matthew.” Canonical Luke is dependent on “interim Mark” and “proto-Luke.”[12]

The Theory of M.-E. Boismard

(5) The Augustinian hypothesis. This is the traditional position held by the Church until the eighteenth century.[13] It was offered by Saint Augustine in his book Consensus of the Gospels 1.2.4. Saint Augustine’s view is that the order of Gospels as it appears in the New Testament is the same as the chronological order of its composition.

Conclusion:

The best that can be taken from the preceding theories is as follows:

- The Gospels are not the starting point of the collected sayings of Jesus.

- There is no acceptable argument for a divine source for the Gospels, so a natural reason for the common material in Matthew and Luke needs to be sought.

- It appears quite plausible to accept the existence of a prior written document that was a source for Matthew and Luke.

- The Q hypothesis is the only plausible theory that explains the word-for-word agreement between Matthew and Luke when they do not follow Mark.[14]

How Did Scholars Arrive at This Hypothetical Q?

After scholars accepted the fact that Matthew and Luke used the Gospel of Mark, based on numerous undeniable signs, they noticed that Matthew and Luke shared common material that does not exist in Mark. The parallelism, which consists of sharing of the majority of the words of the common passages, is extremely clear. This led to the belief that there is a common source for Matthew and Luke, and that this source, as the majority of Q advocates believe, is not an oral tradition; it is a written text in Greek which was quoted word for word many times by the two evangelists. This common text consists of a compilation of Jesus’ sayings, with rare exceptions.

Does the Qur’anic claim make sense?

Is the Qur’ānic perception of the Gospel of Jesus less logical than the other theories? What I think, in the light of existing, concrete evidence, is that the answer is NO, for many cogent reasons.

- All the theories lack direct physical proof. Q and the Jesus gospel are both hypothetical documents, and there is no reference to them in the known ancient writings.

- The Jesus gospel hypothesis shares with most of the other “theories” the belief in an ancient source(s), and agrees with the majority of scholars that that source was a written document.

- The Qur’ānic perception of the matter is not decidedly different from many other academic solutions for the synoptic problem. Here are some examples.

- J. G. Eichhorn, after reiterating G. E. Lessing’s theory and elaborating it, defended the hypothesis that a short historical sketch of the life of Christ, which may be called the Original Gospel, was the basis both of the earlier gospels used during the first two centuries, and of the first three of our present Gospels.[15]

- The Jerusalem school hypothesis, which gives Luke a priority position, was defended as follows by Robert Lindsey, one of the founding members of the Jerusalem School of Synoptic Research: There existed in the beginning a Hebrew biography of Jesus that was translated literally into Greek.[16]

- Philippe Rolland’s theory is based on four sources: A primitive Semitic gospel, two later versions of it, and Q.[17]

- P. Benoit proposes that there was (1) an Aramaic S, which is a collection of Jesus sayings, (2) and an early Aramaic version of Matthew.[18]

- Boismard’s theory is based on a Palestinian proto-gospel hypothesis.

The Qur’ānic alternative surpasses those theories from other angles:

- Most theologians and scholars who are studying the historical Jesus today agree that Jesus was no more than an Israeli prophet.[19] That is a crucial truth that should lead us to deduce that Jesus, in all probability, had his own sacred book, as did many of the other great Israeli prophets.

- The term “gospel” was not used before the emergence of the New Testament as a religious term in the Jewish world. It is stated in the Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament that “the distance between the Old Testament Jewish tradition and New Testament use of εὐαγγέλιον is considerable, particularly in view of the fact that the Hebrew and Greek nouns appear in neither the Masoretic Text nor the Septuagint with a theological meaning.”[20]

- It is very likely that the title “gospel” was not used in the beginning to identify the first “gospels.”[21] The first known author who called these writings “gospels” is Justin Martyr in the second century, and from his statement we can find that this word is a later denotation for one special type of the Christian scriptures. He said that what he calls “Memoirs of the Apostles” are called “gospels.” He wrote in 1Apology 66.3, “In the memoirs which the apostles have composed which are called Gospels “ἃ εὐαγγέλια καλεῖται” they transmitted that they had received the following instructions…” In his dialogue with Trypho the Jew 10:2, he quoted Trypho as saying, “I know that your commandments which are written in the so-called gospel ‘ἃ γέγραπται ἐν τῷ λεγομένῳ εὐαγγελίῳ’ are so wonderful and so great that no human being can possibly fulfill them.”

- The Qur’ān says:

{وَمَا أَرْسَلْنَا مِن رَّسُولٍ إِلاَّ بِلِسَانِ قَوْمِهِ لِيُبَيِّنَ لَهُمْ فَيُضِلُّ اللّهُ مَن يَشَاء وَيَهْدِي مَن يَشَاء وَهُوَ الْعَزِيزُ الْحَكِيم}

“We sent not a messenger except (to teach) in the language of his (own) people, in order to make (things) clear to them. Now Allah leaves straying those whom He pleases and guides whom He pleases: and He is Exalted in power, full of Wisdom.” Q. 14:4

So, the earliest source should be in the lingua franca of Jesus and his people, which is Aramaic (or perhaps Hebrew). Most of the other theories start with a supposed Greek text(s).

- We read in Matthew 26:13, “Verily I say unto you, Wheresoever this gospel shall be preached in the whole world, there shall also this, that this woman hath done, be told for a memorial of her.” (Mark 14:9). It is hard to not think that “this gospel” refers to a real text that the believers and the nonbelievers could read in Jesus’ time.

- It is remarkable that Q contains only the sayings of Jesus, while we know that the sayings of other old and influential historical and mythical characters were circulating, as a whole, in stories and epics. We can say, based on the previous fact, that taking Q to be a primitive collection that is supposed to be a collection of divine commandments for guidance makes a lot of sense, especially in the Israeli prophetic tradition.

To think, as many do, that the Greek Q document is an exact translation of an Aramaic text is hardly plausible; it is more reasonable to propose that the Greek Q is a text that contained part of the first Aramaic gospel through the oral tradition circulating in early times. Excluding the hypothesis of a direct translated Q from an Aramaic precedent is due to the absence of any serious sign of a Semitic autograph.[22] It is most probable to think that the earliest tradition was not transmitted to later generations and communities as a whole package of sayings or deeds, but that that tradition passed to future non-eyewitnesses through the eyes of influential religious characters and groups of their times, who included in their version only what reached them and what they felt to be valuable.

An Untold Story!

But how can we explain the absence of any reference to this gospel in ancient literature?

First: We can give a fully satisfactory answer to the previous question if we can enlighten the whole obscure zone. All that we know about the obscure zone, however, is only a few glimpses, so all that we can say about Jesus’ Gospel is but the outline of its history.

Second: We are unable to draw the exact history of the four existing canonical gospels, so we would be, without a doubt, less successful in discovering the minute details of the period that preceded it.

Third: The absence of any mention of the divine gospel of Jesus is no stranger than the absence of the mention of Jesus himself in any historical, non-Christian, document of the first century.[23]

Fourth: The prologue to the Gospel of Luke tells us that in the early decades of the second half of the first century, many writings that tell Jesus’ story did exist, but today we know nothing of those well-known writings. This tells us that when studying very early Christianity, we should not be tied too much to concrete documents, because that will lead to the loss of many attainable truths.

Fifth: We can say about Jesus’ lost gospel what was said by John S. Kloppenborg, one of the most famous proponents of the existence of Q: “Q is neither a mysterious papyrus nor a parchment from stacks of uncataloged manuscripts in an old European library. It is a document whose existence we must assume in order to make sense of other features of the Gospels. […] Scholars did not invent Q out of a fascination for mysterious or lost documents. Q is posited from logical necessity.” [24]

Why Must Scholars Go Beyond Q?

There are many solid reasons:

First: As shown by recent studies, Q is not a new document; it has its own history, as do the canonical gospels. It is a growing entity that starts from an early collection of existent materials that was circulating in the primitive Christians’ communities after Jesus’ disappearance, and was enlarged when more traditions were added to it. So we have to get to its very beginning to reach the fountain of Jesus’ message.[25]

Second: The astonishing diversity of the traditions circulating in the early Christian communities leads us to consider that there was possibly an early corruption that started soon after Jesus’ ascension or possibly before that. Such corruption would make it unwise to take the common texts of Matthew and Luke as the earliest Jesus tradition or conflated tradition. We should accept two hypotheses: (1) an early wave of corruption; (2) Q does not represent the entire, true early tradition.[26]

Third: Q fails to offer a whole picture of the message of Jesus; it fails to show Jesus as an Israeli prophet sent with a dynamic earthly message. Jesus of Q is minimized to an eschatological prophet,[27] or a sapiential sage.[28] He lost much of what we would expect from such an influential figure, because, in accord with the traditions of the nation of Israel, rules of daily life are an essential component of the message of the prophet or reformer, even one who is concerned about heralding the end of time.[29]

We can conclude by stating that Christians lost Jesus’ gospel in the darkness of the first half of the first century, within a short time after his ascension, and then they lost the autographs of the New Testament as soon as these books were written. It is one of the grievous tragedies of history.

- See F.J.M., “Gospel, Gospels,” in Paul J. Achtemeier et al., eds. Harper Collins Bible Dictionary, revised edition, San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1996, p. 385 ↑

- See also J. K. Elliott, “Mark and the Teaching of Jesus: An Examination of ΛΟΓΟΣ and ΕΥΑΓΓΕΛΙΟΝ,” in William L. Petersen, John S. Vos and Henk j. de Jonge, eds., Sayings of Jesus: Canonical and Non-canonical: Essays in Honour of Tjitze Baarda, pp.41-5 ↑

- See Trent C. Butler, ed. Holman Bible Dictionary, Nashville: Holman Bible Publishers, 1991, pp.1291-292 ↑

- Gerhard Kittel, ed. The Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, tr. Geoffrey W. Bromiley, Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1968, 5/803-804 [italics mine]. ↑

- Daniel B. Wallace, The Synoptic Problem, [italics mine].http://bible.org/article/synoptic-problem (6/30/2011) ↑

- James M. Robinson, The Gospel of Jesus, A Historical search for the original good news, New York: HarperCollins, 2006, p.4 ↑

- W.S. Vorster, “Through the Eyes of a Historian,” in Patrick J. Hartin and J. H. Petzer, Text and interpretation: new approaches in the criticism of the New Testament, Leiden: Brill, 1991, p.23 ↑

- See David E. Aune, ed. The Blackwell Companion to the New Testament, p.243 ↑

- Austin Farrer, “On Dispensing with Q,” in D. E. Nineham, ed. Studies in the Gospels, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1967, p. 62 ↑

- See W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem: A Critical Analysis, New York: Macmillan, 1964; repr. Western North Carolina Press, Dillsboro, NC , 1976 ↑

- See P. Benoit and M. – E. Boismard, Synopse des Quatre Evangiles en Français avec parallèles des apocrypes et des pères, Vol. 2, Paris: Les Editions du Cerf, 1972; Paul J. Achtemeier with others, ed. Harper Collins Bible Dictionary, p. 1082. ↑

- David E. Aune, ed. The Blackwell Companion to the New Testament, p. 248 ↑

- For the Church Fathers’ views before Augustine, see Cl. Coulot, art. “Synoptique,” in Jaques Briend et Michel Quesnel, eds. Dictionnaire de la Bible, Paris: Letouzey, 2005, 13/790-91 ↑

- Marcus Borg estimated that ninety percent of contemporary gospel scholars believe in the existence of Q (See Marcus Borg and others, eds. The Lost Gospel Q, the Original Sayings of Jesus, Berkeley: Ulysses Press, 1996, p.15) ↑

- See Andrews Norton, The Evidences of the Genuineness of the Gospels, Boston: J. B. Russell, 1837, 1/9 ↑

- See Robert Lindsey, “A Modified Two-Document Theory of the Synoptic Dependence and Interdependence,” in Novum Testamentum 6 (1963), pp.239-63. ↑

- See Philippe Roland, Les Premiers Évangiles, Un Nouveau Regard sur le Problème Synoptique, Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1984 ↑

- See P. Benoit, “Les Évangiles Synoptiques,” in La Bible de Jérusalem, Paris, pp.1407-413. ↑

- John Hick, in his “The Metaphor of God Incarnate: Christology in a Pluralistic Age” (London: Westminster John Knox Press, ٢٠٠٦, p.٢٧) writes, “A further point of broad agreement among New Testament scholars […] This is that the historical Jesus did not make the claim to deity that later Christian thought was to make for him: he did not understand himself to be God, or God the Son, incarnate. […] such evidence as there is has led the historians of the period to conclude, with an impressive degree of unanimity, that Jesus did not claim to be God incarnate” ↑

- H. R. Balz and G. Schneider, eds. Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004, 2/71 ↑

- See Helmut Koester, “From the Kerygma-Gospel to Written Gospels,” in New Testament Studies 35 (1989), pp.361-81, for the fuller account of the arguments. ↑

- After an in-depth study, N. Turner concluded that Q language “offers appreciably from the typical translation Greek of which there are abundant examples in the Septuagint” (“Q in Recent Thought,” in Expository Times, 80 (1969), p.326). And that “the Semitic element is not too pronounced in the sections of Matthew and Luke usually ascribed to Q, and no evidence demands a translation hypothesis” (p.328) ↑

- See Earl Doherty, Jesus Neither God Nor Man, the Case for a Mythical Jesus, Ottawa: Age of Reason Publications, 2009, pp.503-656 ↑

- John S. Kloppenborg, Q, the Earliest Gospel, an Introduction to the Original Stories and Sayings of Jesus, Louisville, London: Westminster John Knox Press. 2008, p.4 ↑

- See Marcus J. Borg, The Lost Gospel Q: The Original Sayings of Jesus, Berkeley: Ulysses Press, 1996 ↑

- Even John S. Kloppenborg states, “It is illegitimate, therefore, to argue from silence that what is not in Q was not known to the editors or, still less, that what is not in Q cannot be ascribed to Jesus.” John S. Kloppenborg, “The Sayings of Gospel Q and the Quest of the Historical Jesus,” in The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 89, No. 4 (Oct., 1996), p. 330 ↑

- See John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: rethinking the historical Jesus, II, New York: Doubleday, 2004; Bart Ehrman, Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1999 ↑

- See Ben Witherington III, Jesus the Sage: The Pilgrimage of Wisdom, Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994 ↑

-

Such as the Essenes; see Joseph M. Baumgarten (tr. Christophe Batsch), “La Loi Religieuse de la Communauté de Qoumrân,” in Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, 51e Année, No 5 (Sep. Oct., 1996), pp.1005-025